eDiscovery Australia

eDiscovery Australia: A current snapshot

Technology has changed the way we do business. It has also changed the volume of information businesses create each year and this is leading to an ever-increasing number of documents involved in legal proceedings.

It is estimated that 93% of all documents are digital, so it follows that the vast majority of discoverable documents will be electronic.

In response to the changing evidentiary landscape, Australian courts have embraced technology. Federal Court Practice Note (GPN-TECH) states,

‘The Court embraces the use of technology in proceedings and in its wider operations.’ (1.2)

The practice note goes on to explain that ‘electronic discovery’ is one of the uses of technology the court endorses.

The rapid adoption of technology is also driven by the need for improvements in time and spend for the Australian legal industry. The courts or regulators set tight deadlines and there is a need for law firms to be cost-effective and have a proportionate spend on their eDiscovery.

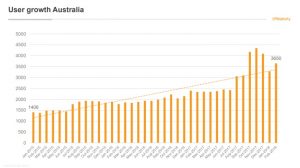

This top-down push towards technology is clearly shown in the data. Leading eDiscovery software platform, Relativity has seen tremendous growth in the Australian market. The number of Relativity users doubled from 2015 to 2018 and has continued to grow exponentially ever since.

This top-down push towards technology is clearly shown in the data. Leading eDiscovery software platform, Relativity has seen tremendous growth in the Australian market. The number of Relativity users doubled from 2015 to 2018 and has continued to grow exponentially ever since.

This rapid growth has also driven significant upskilling and innovation in the region. The number of professionals obtaining Relativity certifications in APAC grew by 40% (which is twice the global average for context). There were also three Australian finalists in the Relativity Fest 2021 Innovation awards, proving the country is over-performing on the international eDiscovery stage.

This evolution of the legal industry means it is essential that lawyers are proficient in eDiscovery principles, processes & practices.

Areas such as forensic data collection and comprehensive digital analysis of big data sets require a skill set that is beyond most lawyers. To successfully run a litigation case, lawyers hire actuaries, appraisers and accountants – eDiscovery professionals should be considered in the same terms. Technical experts can be crucial to defending methodologies chosen during the collection of evidence or document review stage.

The volume of material lawyers need to deal with means efficient and defensible culling of that material before incurring the costs of processing those files is how smart firms are dealing with this data growth.

While hiring a technical expert ensures the efficient use of technology, there is still a heavy onus on lawyers to understand the regulation and practice of eDiscovery in Australia.

eDiscovery Australia: The Current Position

eDiscovery Australia: The Current Position

1) Mobile Devices

Any data stored on a mobile device – and the device itself – are considered a ‘document’ for the purposes of discovery in every Australian jurisdiction.1 Each party’s discovery obligations are defined by a relevance test and whether the mobile device is in the party’s control.

Test for relevance

The test for relevance varies for each jurisdiction and includes:

- NSW – Is the document relevant to the fact in issue? Could it rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the fact (regardless of whether admissible as evidence)?

- Fed & VIC – Does the party intend to rely on the document or could it adversely affect/support the party’s own or another party’s case?

- QLD – Is the document directly relevant to an allegation in the pleadings?

- ACT – Does the matter directly or indirectly relate to a matter in issue in the proceeding?

- WA – All documents relating to any matter in question are discoverable.

Test for control

The test for determining whether a mobile device is in a party’s control also varies in each jurisdiction.

- Fed, VIC, NSW and WA define control as ‘possession, custody or power*‘.

- ACT as ‘custody and power*‘.

- QLD as ‘possession or under the control’;2 the interpretation of ‘control’ appears similar.3

‘Power’ is held to be an enforceable legal right to inspect the document without the need to obtain consent from anyone else, regardless of the fact that for physical reasons the party cannot immediately inspect. If the employer owns the legal device, regardless of it being in an employee’s possession, that device is within its ‘power’ and therefore discoverable in most jurisdictions. If the employee owns the device, the question of control of the data will depend upon where the data originated, on what basis it was provided and the scope of the employer’s ICT policies regulating the use of personal mobile devices. The interpretation of ‘control’ appears similar.4

2) Cloud Computing

The issue of discovery and cloud computing has yet to be tested in an Australian court, however the obligation to discover documents hosted in a cloud environment would be subject to the test of relevance and control discussed above. If a party had an agreement with a cloud provider to retrieve documents without the provider’s consent, then presumably a court would consider those documents within that party’s ‘control’ or ‘power’.

In the event the cloud environment is located outside of Australia, other regulatory factors such as local data privacy rules would have to be considered.5

3) Pre-discovery Conference

Most Australian courts have practice guidelines relating to the discovery of electronically stored documents. In the Federal Court for example, Technology and the Court Practice Note (GPN-TECH) at 3.3 states that parties are expected to have:

(a) discussed and agreed upon a practical and cost-effective discovery plan having regard to the issues in dispute and the likely number, nature and significance of the documents that might be discoverable; and

(b) conferred for the purpose of reaching an agreement about the protocols to be used for the exchange and management of documents in electronic form and other issues relating to efficient document management in a proceeding.

The courts take these pre-eDiscovery conference rules seriously as evidenced in ASIC v McDonald.6 In this case the court disallowed the plaintiff’s key evidence because it had been acquired in breach of an agreed upon search methodology – a laptop outside of the parties pre-discovery agreement.

4) Lawyers Duties – Reliance on keyword search is dangerous

Keyword searches are a common practice in eDiscovery but are keyword searches sufficient to satisfy legal obligations?

In Qualcomm Inc. v Broadcom Corp, the plaintiff failed to do a certain keyword search on email archives of their witnesses which resulted in them failing to exchange discoverable documents. The court found it ‘incredible that Qualcomm never conducted such an obvious search for key terms.’

This case highlights that a parties’ ability to pick the right keyword search terms for documents may not be as easy as the court assumes. This is supported by a study that discovered people searching others’ work are very poor at guessing the right words to use in a search.7 The study of lawyers and paralegals specialising in subway accidents revealed that following a search of 40,000 documents participants were certain they had found at least 75% of the relevant documents, but they had in fact, only located about 20% of relevant documents.

In Australia, lawyers have an ethical duty to ‘deliver legal services competently, diligently and as promptly as reasonably possible’8 and this obligation extends to eDiscovery.

By relying exclusively on keyword searches during discovery, a lawyer may fail to satisfy their obligations of competence and diligence.

Technical experts use SaaS-based eDiscovery platforms such as RelativityOne and Nuix Discover. The software is integrated with a variety of analytics features such as email threading, concept searching, textual near-duplicates and AI-powered machine learning to ensure that document review is conducted to the highest professional standards.

5) Predictive Coding – McConnell Dowell Constructors (Aust) Pty Ltd v Santam Ltd & Ors (No. 1),1 Vickery J

The Australian courts are very progressive in their attitudes towards the use of technology and this is clearly seen in the introduction of Practice Notes in Victoria9 and the Federal jurisdictions10 approving the use of technology-assisted review (TAR).

The Federal Practice Note on Litigation using Electronic Discovery lists search strategies such as predictive coding, email threading, keyword/concept searching and de-duplication as appropriate uses of technology.11

The Victorian Practice Note echoes Justice Vickery’s ruling in McConnell Dowell Constructors v Santam Ltd Ors12 stating that ‘the Court may order discovery by technology-assisted review, whether or not it is consented to by the parties.’

This presents opportunities to make use of a full suite of analytics features during eDiscovery with the Court’s consent.

eDiscovery Australia: Conclusion

In Australia, legal technology and technology-assisted review (TAR) have moved into the mainstream of legal practice.

Courts have imposed strict guidelines so that any case involving more than 200 documents must be conducted by eDiscovery and the Court may order parties to use TAR whether they consent or not.

The changing legal landscape offers a great opportunity for lawyers who are willing to invest in their technology skills to learn from and work with leading eDiscovery professionals.

If you would like to develop your eDiscovery service offering, book a consultation with one of our technology experts today.

- Palavi v Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 264

- Lonrho Ltd v Shell Petroleum Co Ltd [1980] 1 WLR 627, 635 per Lord Diplock

- Steele Software Systems, Corp. v. DataQuick Information Systems, Inc., 237 F.R.D. 561, 564 (D. Md. 2006

- Steele Software Systems, Corp. v. DataQuick Information Systems, Inc., 237 F.R.D. 561, 564 (D. Md. 2006)

- http://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/files/20150529-eDiscovery-around-the-globe-whitepaper-129403.pdf

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Macdonald, No. 5(No 5) [2008] NSWSC 1169 (NSWSC November 4, 2008)

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/91f7/579e660c139cb971f37f87c2dc0d3c86b9c6.pdf

- Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015 (NSW), 4.1.3

- SC GEN 5 Technology in Civil Litigation 8.7 – Vic Supreme Court – https://www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/law-and-practice/practice-notes/sc-gen-5-technology-in-civil-litigation

- Technology and the Court Practice Note (GPN-TECH), Federal Court, http://www.fedcourt.gov.au/law-and-practice/practice-documents/practice-notes/gpn-tech/electronic-discovery

- Litigation using Electronic Discovery, Federal Court, http://www.fedcourt.gov.au/law-and-practice/practice-documents/practice-notes/gpn-tech/electronic-discovery

- McConnell Dowell Constructors (Aust) Pty Ltd v Santam Ltd & Ors (No 1) [2016] VSC 734 (2 December 2016)